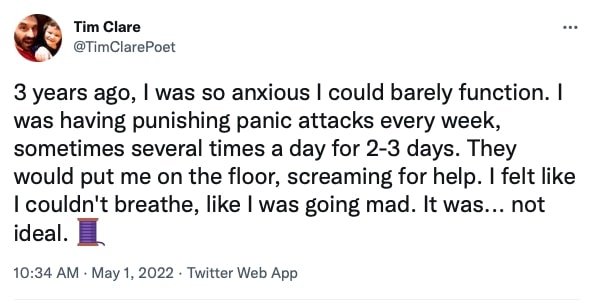

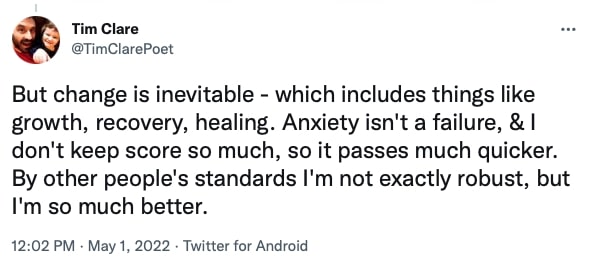

Tim Clare is anxious. He has spent the better part of a decade wrestling with panic attacks and chronic worry. Having struggled to find treatment that worked, and with his family increasingly concerned for his wellbeing, Clare decided to make it his professional mission to get better, trying cures as varied as cold-water swimming, psychedelic drugs and hypnosis in a bid to learn how to cope with anxiety.

The result is Coward: Why We Get Anxious and What We Can Do About It, a book by turns brutally honest and hilarious. Clare’s dedication to his subject is hugely impressive, with in-depth interviews with leading mental health experts and first-person experiences that many would baulk at.

The result is something wholly unique. It’s not self-help, says Clare, rather his way of acting as a guinea pig for anxiety sufferers everywhere.

“I think a lot of my coping strategy has been trying to cheapen my pain by turning into a product I can sell,” he jokes. Though it did have a serious purpose. Writing it down, he says, was a way of motivating himself to get better.

These are some of the treatments he tried and how they affected his anxiety…

Exercise and diet

We all know that eating well and moving more are good ideas. But in and of themselves, says Clare, they did not prevent him from feeling anxious.

“Exercise and a better diet are not going to cure someone’s anxiety, unless they have it very mildly,” he says. “I would say they are great foundational things that make it easier for the other stuff to work.”

But that doesn’t mean they don’t have value. Over the course of a few months, Clare began eating a vegan diet and started running daily. He lost three stone and ran a marathon.

“That was a great confidence builder for the other work that I did on myself,” he says, “because I never thought I could do that. I would never have believed I could have changed my diet or run that far, but I did.

“Then I started thinking, Well, if I can do that, is it possible that I’ll be able to not be anxious in certain situations? That is quite a persuasive thing to have knocking about in your head.”

And even if exercising more and eating well don’t improve your anxiety, there are still clear benefits, he says: “The worst that ever happens when you’re doing these things is that you’re making it less likely that you’ll get long-term health problems.”

Psychedelics and antidepressants

Clare has been taking antidepressants for most of his adult life. But for his book, he wanted to try drugs that have enjoyed plenty of coverage in recent years: psychedelics.

A growing body of research from institutions including Imperial College London and New York University suggests that drugs including MDMA and psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms, can alleviate anxiety and depression. He had pinned much of his hopes on ending his anxiety onto this increasingly popular cure.

In order to do so, he had to come off of his antidepressants, which inhibit the reabsorption of serotonin in the brain. Psychedelic drugs increase serotonin’s release, meaning that when both drugs are taken together, they can cause serotonin syndrome, causing tremors, a racing heart and potentially death.

Clare placed much hope in these drugs, taking psilocybin under supervision in the Netherlands. “I was flying through tunnels,” he says. “I met an angel who spoke to me. My body exploded. The dead came back to life and spoke to me. The room filled with water and I was a jellyfish swimming through it.”

Clare was told that afterwards he would be in a heightened state of consciousness and that his anxiety would be alleviated. The reality was the complete opposite. “I felt like I was having a massive comedown,” he says, and he broke down in tears with his wife, as he explained that all his hopes that psilocybin would cure his anxiety had come to nothing.

Clare points out that a Johns Hopkins study that claimed to prove the efficacy of psilocybin in a double-blind trial was problematic. “You can’t have a real control group when you’re doing psychedelic studies with high doses,” he says. “When you take a load of magic mushrooms, you can’t be in the control group and not know.”

Clare points out that prescription antidepressants such as sertraline have a far better efficacy rate compared with psychedelics. He still takes his medication daily.

Cold-water immersion

Swimming in icy rivers might hold an appeal for a certain subset of hardy souls. But Clare was keen to get beyond the nature communion aspect and consider cold-water immersion in a wider context. He began by taking cold showers and baths, first following renowned ‘Iceman’ Wim Hof’s cold-water immersion and breathing techniques.

Hof’s methods – which involve exposing yourself to the cold, either in a bath, shower or outdoor setting; and taking sharp breaths before breathing out and not breathing in for anything upwards of a minute – have gained a legion of fans who say it has eased the release of stress hormones and lessened their anxiety.

RELATED: The Science Of Cold-Water Immersion

Clare says the cold allowed him to see his anxiety coming, watching like an observer as a panic attack washed over him before realising it had passed. Then he went swimming.

“I spoke to a few researchers, including Mark Harper and Dr Chris Van Tulleken,” he says, “who did a small study for a BBC show called The Dr Who Gave Up Drugs.”

This study in cold-shock response suggested repeated exposure to cold water could reduce inflammation, which is a cause of anxiety and depression. The same, brief exposure to something dangerous is the same principle behind vaccines, says Clare.

“I did the protocol in [Harper’s] paper, which is six consecutive days with three minutes, where the water temperature is around 14 degrees.”

He warmed up after his swims by running alongside the river near his home. Clare says in that moment he felt centred and calm. ‘I enjoyed the experience,’ he writes. ‘It felt meaningful to me.’

Hypnosis and hypnotherapy

In Coward, Clare writes that hypnosis exists in a ‘no man’s land’ between legitimate treatment and alternative medicine. There is, he says, scant evidence that hypnotherapy works better than placebo treatments. Yet, it was hypnosis that he says had the most marked, long-term effect on his anxiety:

“I am not saying that hypnotherapy is a well-evidenced intervention for anxiety. However, I have to report for the sake of honesty that I went to four sessions of it and I’ve never had a panic attack since. I think it may be as simple as during those sessions I was encouraged to talk about my feelings.

“That you do so under supposedly hypnotic state conditions means it can be especially easy to talk about embarrassing or traumatic things.”

Ultimately, says Clare, he felt understood when he went for hypnotherapy. More than trying to understand the physiology of a panic attack, he believes that being believed and heard when discussing such intimate feelings and what triggers them is key to dealing with anxiety.

“Until you feel, at some level, your anxieties have been listened to and that the message has been received,” he says, “it’s not going to go away.”

Words: Joe Minihane