I’d always had a love-hate relationship with running. Playing sport was never an issue, but I’d try my hardest to get out of long runs that didn’t involve a ball.

As I crept towards the big four zero, however, and got tired of 18-year-olds running rings around me at football, I knew I’d have to find another way of getting exercise in.

It was late on a Saturday night, edging into Sunday morning. I’d finished work and had jumped on the train to my local station.

Sat in a warm carriage, I peered through the window. The rain was horizontal and the wind whipped the trees back and forth. I was praying there would be a string of cabs in the taxi rank. There wasn’t.

Standing in the deserted ticket hall, I steeled myself for the inevitable drenching. All that separated me from my warm, inviting bed was two miles of hilly, dark, wet countryside.

With the thought of fresh, cosy sheets lingering in my mind, I’d no option but to walk. Shouldering my rucksack, I strode out towards home.

I got back 45 minutes later, miserable and soaked. But as I towelled myself off, I wondered whether walking with a load on your back could be considered an alternative to running. It turns out, it can.

What is rucking?

Put simply, rucking is a resistance exercise where you carry the weight in a rucksack while walking. It doesn’t get more complicated than that.

It doesn’t have to be a long walk. You don’t have to carry a heavy weight, you don’t need expensive equipment and you don’t have to learn any complicated techniques. The beauty of rucking lies in its simplicity.

With the added weight, your legs, core, back and shoulders have to work harder to keep you moving. As such, you’ll burn more calories while strengthening your whole body.

Its popularity in the United States has spawned numerous websites, podcasts and clubs. Although it isn’t as big on these shores, rucking’s reputation is growing slowly as people look to explore the great outdoors.

Origins of rucking

We can trace rucking back to the Roman Empire. Vegetius, the Roman theorist, wrote in his book De Re Militari, ‘The first thing the soldiers are to be taught is the military step, which can only be acquired through constant practice.’

He believed that a Roman soldier should be able to march 20 miles in five hours, while carrying 60lbs of equipment, as a basic standard of fitness.

Despite nearly 1,600 years passing since Vegetius’ words, the need for a human to walk long distances while carrying heavy loads hasn’t diminished. In fact, a 2016 article published in The American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine noted that ‘Early humans may have walked 12 miles a day finding food, exploring and seeking shelter.’

It goes on to say this exercise ‘provided our muscles and bones with abundant physical activity’ while supplying ‘our brains with enough oxygen for continued neuronal development.’ Plainly, it’s in our DNA to move.

It’s also better for your joints than other forms of exercise. According to a study published by the British Journal of Sports Medicine in 2007, “the reported incidence of running injuries to the lower extremities in long distance runners varied from 19.4% to 92.4%.” Worryingly, up to 50% of these injuries were knee-related.

Compare these figures to a study in the American Medical Journal, which found that most injuries suffered by ruckers were blisters.

Photography: Getty Images

Benefits of rucking

Many associate the effectiveness of exercise with how many calories you burn, but there are more benefits to rucking than physical fitness. It can enhance your mental health as well.

Chris Spray is the co-founder of Mind Over Mountains, a charity that helps people heal through the power of nature. Formed in 2018, it holds organised rucks through the mountains and aims to be accessible to all.

As a neuro linguistic programmer, he’s well aware of the calming effects of time spent in nature. “We live our lives on a conveyor belt,” he says. “Quite often people come out with us and improve. Sometimes they just like to come and talk.”

Despite my only real involvement of rucking being a soaked walk home, I wanted to go on a proper ruck. Plan a route, carry a weight and see how I got on both physically and mentally.

Getting started with rucking

I recruited a good friend and experienced rucker, Paul, to come along for support, but to also tap into his knowledge. I dusted off an old backpack found in the loft. It was sturdy, had chest and waist supports and was deep enough to support the weight, water and snacks I’d be carrying. Paul said he’d sort out a weight to carry.

On the day of our ruck, he was sat outside his house waiting for me, with two ominous blue rubble bags resting at his feet. He smiled as I cast my eyes warily over them. Inside each was 10kg of shingle. With one deposited into my pack, we drove out into the countryside.

Reaching the start point, I donned the rucksack. I could feel the weight sitting at the bottom of the bag, pulling the shoulder straps sharply into my skin, dragging me off balance. It was an easy mistake to make, one that could’ve made it harder for my body to compensate for.

Mike Chadwick is a strength and conditioning coach who spent 13 years in the Parachute Regiment and Royal Army Physical Corps. He now runs coachmikechadwick.com, an online coaching academy for tactical athletes. His clients range from international Special Forces to UFC fighters. With his past experiences, he certainly knows a thing or two about rucking.

“You’re less efficient if the load is away from your centre of mass,” Chadwick says. “The best thing to do is have a backpack that sits flat against your back, which also has chest supports.”

Space to talk

A quick re-pack, with the weight sitting higher up, and we were off. We rolled through lush meadows and hefty hills at a gentle pace, the sun’s rays beating down on us.

Within 20 minutes of being in the countryside, I started to notice a difference. Although my calves were burning from the added weight and undulating terrain, I felt something else. My mood had lifted. I’d opened up to Paul and we spoke freely about everything and anything. As we talked, all thoughts of burning thighs and chafing shoulders melted away.

Chris Spray knows exactly why I felt like that. “When we walk alongside one another and just listen, we’re actually giving back,” he says. “The psychological effect of meeting friends can lead to your heart rate elevating, while stress chemicals are decreased.”

Mental health benefits of rucking

In some ways, this aspect of rucking was more important to me than burned calories or distance travelled. It’s supported by science as well. The same article published in the American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine says, ‘Time in nature can lead to health benefits’, such as ‘restoration of mental and emotional health.’

We rucked for just under six miles. I asked Chadwick whether this was long enough.

“Your distance should be determined by your competence,” he says. “Your competence is determined by your foundations.”

Is there anything in the gym I could do to help, I ask? He’s quick to point out that core stability is the key, and a heavier load requires greater core strength.

While rucking is straightforward and cheap, it’s a good idea to invest in a suitable backpack. A 2018 study published in the Military Medical Research Journal looked at how the positioning of a load on a ruck affected the human body.

The results showed that soldiers expended more energy, took more breaths per minute and ultimately had a higher heart rate when marching with their kit distributed across the body. They found the opposite when the soldiers carried the kit on their backs.

Ruck on

You can do rucking anywhere – you don’t have to do it through fields or meadows or take on steep hills. In fact, if you’ve ever decided to walk from point A to point B with a backpack, you’ve rucked.

At the end of my outing, despite aching muscles, I felt good. I was sweating and my mind was clear.

Spray reminded me that 80% of the challenge in addressing your wellbeing is actually just turning up. The rest is easy.

Rucking equipment

Mirafit Cast Iron Ruck Plates

Tins of beans are the budget-friendly way to add weight to your rucksack, but for a more measured approach, these specialist ruck plates allow you to know exactly how much load you’re lugging. When you’re done rucking, they make for useful resistance training accessories, too – like odd-shaped weight plates. They’re available in 5kg, 10kg, 15kg, 20kg or as a full set.

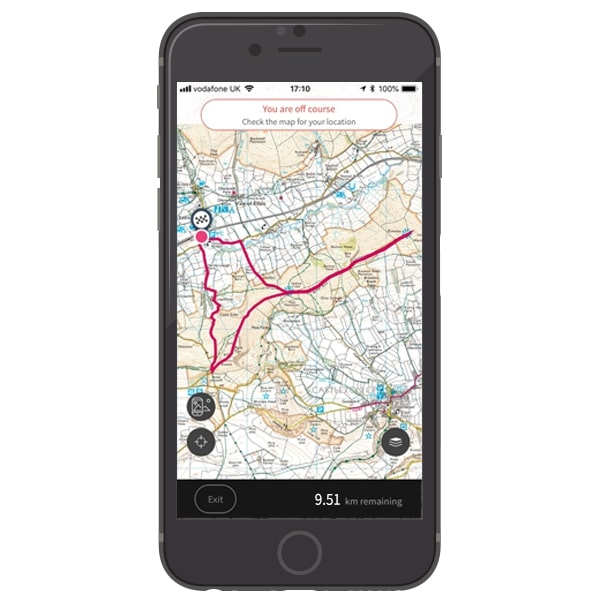

GPS Apps

For longer rucks, a map and compass are the old-school essentials, but for 21st century navigation, download a GPS app like OS Maps or Outdooractive. With an annual subscription, you can plot routes, download offline maps and pinpoint your location – it’s like Google Maps for the countryside.