Anorexia is a complex psychological disorder with a variety of causes and symptoms. Dave Chawner, professional comedian and author of Weight Expectations: One Man’s Recovery from Anorexia, sheds some light on this often misunderstood mental illness.

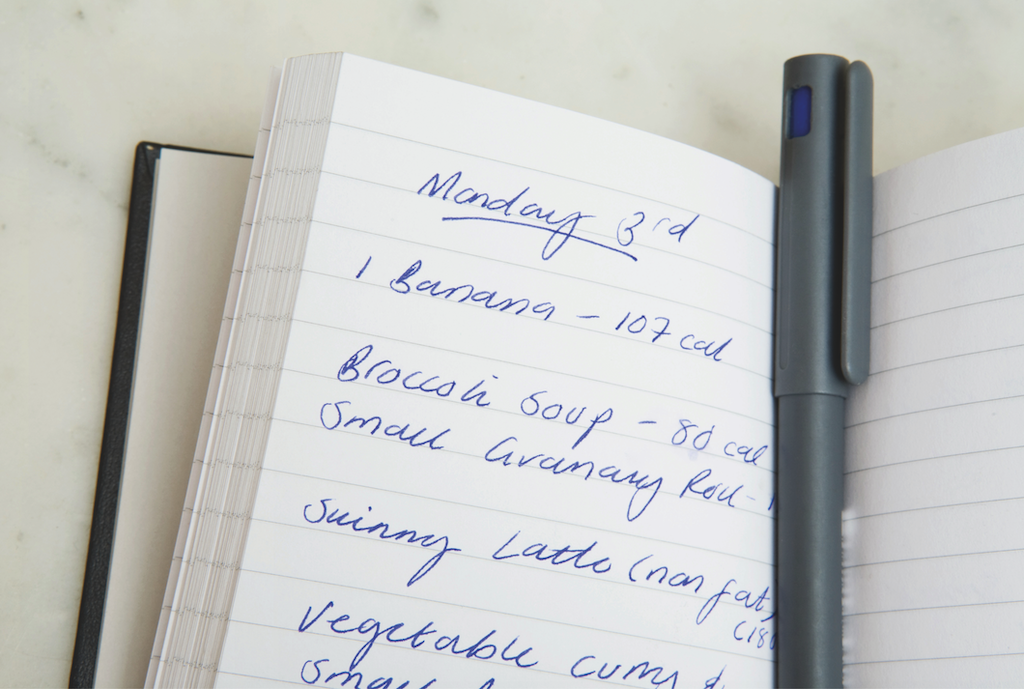

Obsessive calorie counting can breed an unhealthy relationship with food

It’s early in the year, and we all know what that means – everyone is on a diet!

Last year an estimated 28 million of us tried to lose weight in January. And as we get increasingly bombarded with slimming messages, it’s increasingly harder to tell when someone has developed an eating disorder.

It’s estimated 1,250,000 people in the UK have an eating disorder. Around 25 per cent of those are male. According to 2018 stats from the NHS, the number of young men in hospital with eating disorders increased by 98 per cent between 2010 and 2018, which means it’s growing at a faster rate for boys than girls. However, until very recently, that’s just not something that has been focused on.

There’s a lot of misconceptions about male anorexia. It can be seen as a ‘female disease’, but that’s odd when you consider that the first medical description of anorexia was actually a bloke. Not only that, but that was well over 300 years ago, so eating disorders are definitely not ‘new’ illnesses that have been created with the invention of social media.

Sense of Control

My own anorexia took a long time to develop and it took even longer for me to realise that I had a problem. Other people noticed things weren’t right before I did. Sometimes you’re too close to your experiences to have any perspective; you can be too caught up in your own life to be able to stand back and take stock.

If I had to pick a ‘beginning’ it would be 2006. I’d just got a role in a school play where I had to appear topless. So I decided to lose a little bit of weight, but as I began slimming down people kept on telling me I looked ‘good’.

That was the word they kept repeating over and over again: ‘good’. The more weight I lost, the more impressed people were and the more they congratulated me. That gave me a boost, because who doesn’t like being told they’re doing well?

At this point, I want to stress, despite how it sounds, the anorexia wasn’t about vanity. None of it was really about how I looked. As I lost weight people were complimentary and encouraging. They started seeing me as ‘good’. That bought me validation; for the first time in my life, people kept telling me I was ‘good’ at something. They accepted me.

Similarly, around that time I had all the pressures most teenagers have: exams, re-sits, coursework deadlines, applications and University looming. I didn’t deal with it well; everything felt a bit too intense, like it was all piling on top of me and I was getting trapped by my own life.

Over time, restriction, weighing and calorie counting became my subliminal coping mechanisms. I didn’t realise I was relying on them as a distraction from everything I didn’t want to think about. They became something else to focus on. Something that I could manage – that I was in charge of. If I could just focus on all of that stuff, and ‘achieve’ at it, I believed somehow everything would fall into place.

It was above the day-to-day stuff that had been weighing me down, it became more important to me than anything else. It didn’t matter that I did badly at that last exam, as long as I was restricting more, exercising more and weighing less. And when I was reaching these goals, I felt amazing.

That might sound surprising, and I am not glamorising anorexia at all, but it’s important to admit that when I was ‘winning’ at it – when I was able to get under my daily calorie intake, exceeded my quota and ultimately reaching a new low weight – it was something I enjoyed.

“This ‘thing’ that started out as a distraction had become my every waking thought”

Addicted to Weight Loss

I’ve spoken to numerous people about this, even though it’s something that never gets discussed. Jayden Worthington is an 18-year-old who developed anorexia in his late teens. He described his anorexia as ‘a form of addiction’ and told me:

“You end up lying to your family and friends in order to keep things secret. You crave the feeling of emptiness and it’s hard to fight through this. It’s hard, however, because you can’t just avoid food to cope – you have to eat. I spent at least two years of my school life throwing away my lunch and pretending I’d eaten it, I would skip breakfast without my mum finding out or have very little breakfast. I’d say I’d eaten with friends when I was out just to avoid having dinner later on. Anorexia makes you lie to everyone.”

Personally, I loved the buzz of losing weight, restricting food and exercising. I got a short-term enjoyment out of the sensation of feeling lithe, waif and emaciated. And that’s exactly what it was: a ‘short-lived’ enjoyment with long-term consequences. I loved it so much I didn’t realise

I had a problem. I didn’t realise I was anorexic.

The ‘wins’ got harder to get. I had to restrict for longer, exercise more, get below my target weight. Like many addictions, I didn’t realise that I was out of control. That I’d gradually become overwhelmed by anorexia. That this ‘thing’ that started out as a ‘distraction’ had become my every waking thought.

Cumulatively, over time I realised that I might not be as in control as I thought, but there was no way I was going to look to get rid of it. I thought the anorexia was helping me make sense of everything rather than holding me back. And, sure, in those early morning hours where I couldn’t sleep because I was counting up the previous day’s calories and exercising to try to burn them off, I felt guilty at the thought of going to a doctor about it.

Not only that, I was terrified of going to the GP and them laughing me out the door. Maybe they’d tell me I wasn’t anorexic; that I wasn’t skinny enough; that men don’t get anorexia; or that I was making something out of nothing. I didn’t realise how much it had taken over.

Seeking Support for Anorexia

It took me years to get help, and even then I went to the doctors for depression. I’d started feeling numb, not getting any enjoyment out of anything, not being able to sleep, unable to concentrate and constantly feeling drained of energy.

I’m not the only one. I spoke to James, a 30-year-old yoga teacher from Wales. He’s had an eating disorder for the past 15 years. He told me he had a very similar experience:

“There have been times when I have been getting worse and put off going back to the GP to try and get more help or ask to see a specialist. Sometimes this has been because I have been really ambivalent about getting better. I’ve felt like the eating disorder has always been there for me, and that without it I wouldn’t be able to cope.”

That’s something I can definitely relate to. In fact, I refused treatment for anorexia four times. I was terrified of taking it away, worried that nothing of ‘me’ would be left. That sounds stupid now, but at the time it made complete sense.

In the end, my doctor explained that the brain had no energy to release the ‘feel-good chemicals’. She explained that I wouldn’t expect my laptop to work if I didn’t power it, so why expect my brain to do the same? That was a bit of a turning point for me.

You might be confused reading this, wondering why anyone would ever put off getting help. James spoke about his eating disorder as “a defence mechanism that you don’t want to let go of,” which intrigued me. It seems that people seem nervous about seeking help because we talk about ‘losing’ the anorexia, rather than ‘coping’ in alternative ways. No one wants to lose anything, so understandably it can be anxiety inducing.

If you’re reading this because you can relate to some of the things outlined above, there are some common symptoms to look out for. However, the truth is that everyone is different, so everyone will have a different experience. In the same way that a common cold can affect people in different ways, the same is true of anorexia.

Signs of Anorexia: Changing Relationship with Food

This is probably a good place to start. Rituals such as hiding food, cutting it into small pieces, eating incredibly slowly or chewing food obsessively before swallowing can be a useful red flag that a person’s relationship with food isn’t that healthy.

Having strict ‘rules’ around food is also another potential red flag. James described how his “whole life became organised around food, eating and exercise.” For example, only ever eating low-calorie foods, obsessively counting calories, cutting out certain food groups, or only eating

food from one particular brand.

Just as Jayden Worthington spoke about “lying to [your] family and friends in order to keep things secret,” people with eating disorders can commonly deceive people about their meal times.

Perhaps after meals they might seek ways of getting rid of the food from their stomach, or find ways to counteract what they’ve eaten using diet pills or other methods. They may be constantly talking about meals, cooking or calories, or avoiding dinners or events that involve food. In short, they may be obsessed with food.

Signs of Anorexia: Changes in Behaviour

Despite all that, it’s important to emphasise that anorexia is not all to do with food. You may see fundamental changes in behaviours as well. It could manifest as an obsessive focus on body weight or shape, and an insistence that the person is much larger than they actually are. A lot of people talk about the pursuit of a better body and how ugly they are.

The person could have difficulty concentrating, always being distracted and forgetful. Anxiety is also a very common sign and a constant drive for perfectionism, setting impossibly high standards for themselves. This can contribute towards low self-esteem and confidence issues, which might make the person feel low or depressed.

Yet underneath all of this, it’s very usual for the person not to realise that they have a problem, or perhaps even deny the severity or impact it’s having. Sometimes that can happen even after diagnosis.

How to Get Help for Anorexia

If you are worried about someone, there is help and support out there.

- Beat is the UK’s Eating Disorder Charity. They have wonderful help and resources at beateatingdisorders.org.uk. They have helplines and one-on-one web-chats, both of which run 365 days of the year, as well as support groups and monitored chat rooms.

- There is also MaleVoicED, which is a charity set up to help men with eating disorders. They have lots of help and resources on their website, malevoiced.com.