Lydia Smith explores the growing link between the microbiome – your gut bacteria – and mental health.

We’ve known for a long time that the way we feel affects our guts. Just think about the last time you had a job interview or another situation that made you nervous or anxious. Most likely, you will have felt nauseous, experienced butterflies or suffered a stomach ache.

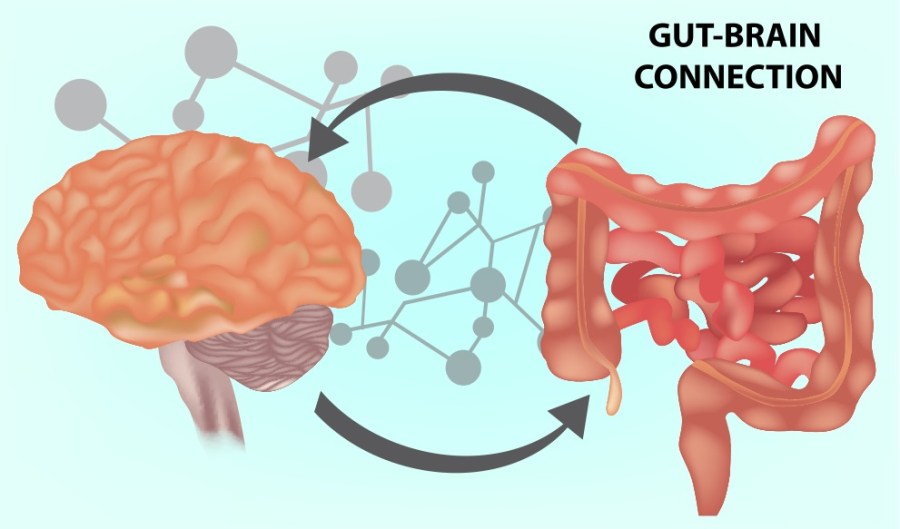

That’s because the brain and gastrointestinal system are intimately connected via the ‘gut-brain axis’ – a fancy term for the communication network that links the pair. A two-way street, the brain is able to send signals to the gut and vice versa.

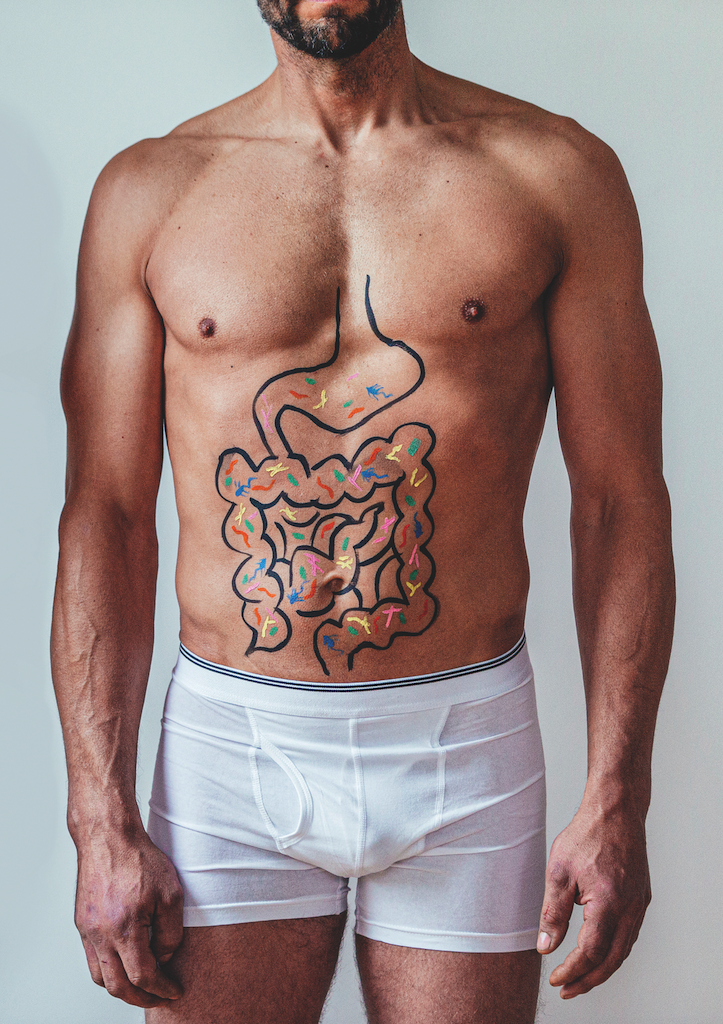

Now, it’s emerging that the ecosystem of bacteria and microbes that live in your digestive tract – known as the gut microbiome – could impact the way you think and feel. Although the gut might not be the first place you think of when it comes to mental health, it may well have a profound influence over your sense of wellbeing.

“What we know is that the gut-brain axis is an area that only recently started getting traction,” says Professor Jeroen Raes, a microbiologist at the University of Leuven and the Flanders Institute for Biotechnology.

“We know that in a great number of mental illnesses – and we’re looking as broad as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, to depression and anxiety – we see studies appearing where the gut microbiota (micro-organisms) are disturbed or altered in patients.”

Bac for Good

Earlier this year, Professor Raes and his team published research that found people with depression had consistently low levels of certain bacteria whether they took antidepressants or not. The researchers drew on medical tests and GP records to look for links between depression, quality of life and microbes lurking in the faeces of more than 1,000 people.

They found that two kinds of bugs, Faecalibacterium and Coprococcus, were both more common in people who claimed to enjoy a high mental quality of life. Meanwhile, those with depression had lower than average levels of the bacteria species Coprococcus and Dialister.

There are a number of animal studies which have strengthened the theory that the bacteria in our gut could have an affect on our mental health, too. In one study, Chinese researchers took a sample of the gut microbiota from patients with major depressive disorder and planted them in germ-free mice. When these mice took part in a ‘forced’ swimming task, they were quicker to quit. This behaviour, researchers suggested, may be linked to the loss of interest and sense of hopelessness associated with depression.

Inflammatory Behaviour

We don’t know exactly how these effects are caused, but Raes explains that there are several theories.

It is thought that gut bacteria may play a part in causing inflammation in the gut, which may lead to neuroinflammation. That has been linked to various mental health disorders, including depression and anxiety.

“In many of those mental health studies, we find changes in the gut microbiota that make us think that inflammation might play a part. We see, for example, a decrease in anti-inflammatory bacteria or an increase of pro-inflammatory bacteria,” Professor Raes says. “One of the theories is that you have intestinal inflammation that is associated or triggered by the gut microbiota and is spread further into neuroinflammation.”

Another theory is that gut bacteria act as a kind of “metabolic factory of chemicals” which could affect mental wellbeing, Professor Raes explains: “In our study on depression, we have shown that many gut bacteria are able to produce and metabolise chemical compounds that have the potential to moderate our nervous system – things like dopamine, serotonin and GABA (Gamma aminobutyric acid).”

These neurotransmitters act as chemical messengers, and are linked to mood and wellbeing. “What we see is that the gut bacteria are able to produce such compounds,” says Professor Raes. “That makes an interesting theory where these compounds could then enter the bloodstream, possibly cross the blood-brain barrier, and affect how our brain develops, or how we think and behave.”

There is also an information ‘highway’ connecting the brain and the gut, called the vagus nerve, which has receptors near the gut lining that allow it to keep tabs on our digestion. In the intestine, microbes release chemical messengers that alter the signalling of this nerve, which in turn affects the brain’s activity.

“The vagus nerve is a big nerve that goes from the intestinal tract straight into our brain,” Professor Raes says. “It’s used as a communication channel in both directions, for the gut to signal to the brain and the brain to signal to the gut, to sense satiety and things like that.

“The idea would be that if the bacteria are able to produce compounds that can signal nerves, it may be that these compounds can put signals on the vagus nerve and then that signal goes into the brain.”

Fermented foods and drinks are packed with gut-friendly probiotics

Turn to the Pros?

In recent years, scientists have begun to explore whether probiotics can play a role in supporting good mental health. These are live bacteria and yeasts promoted as having various health benefits. They are usually added to yogurts or taken as food supplements. They’re often described as ‘good’ or ‘friendly’ bacteria, because they fight against harmful bacteria and prevent them from settling in the gut.

This year, however, a study suggested people who have anxiety may be helped by taking steps to regulate the microorganisms in their gut using probiotic and non-probiotic food and supplements. Researchers reviewed 21 studies that had examined more than 1,500 people, but overall, only 11 studies showed a positive effect on anxiety symptoms by regulating intestinal bacteria.

Professor Julio Licinio, who co-authored the paper linking schizophrenia with an impoverished gut microbiota, says probiotics may have the potential to impact mental health regulating our gut bacteria, but more research needs to be done.

“To ascertain the efficacy of any treatment, including probiotics, rigorous clinical trials are required,” Professor Licinio explains. “I am afraid that probiotics sold over the counter in drug stores or over the internet now have not undergone such trials.”

It is very early days for this research, Professor Raes adds, but says it is the “next generation” of probiotics that may hold more answers.

“The thing that I am excited about is the next generation of probiotics, which is not going to be the bacteria we know from the dairy industry – lactobacilli or bifidobacteria – but rather organisms that have been sourced from healthy humans’ microbiota. In the study on depression, we identified two or three organisms that were depleted in people with depression.”

In theory, he explains, it might be that replenishing those missing organisms may act as a form of treatment in the future. “But we first need to prove the causality before we can make that statement.”

What Makes a Healthy Gut?

Rather than a single species of bacteria being responsible for these effects, researchers believe it is the overall diversity of microbes that is important.

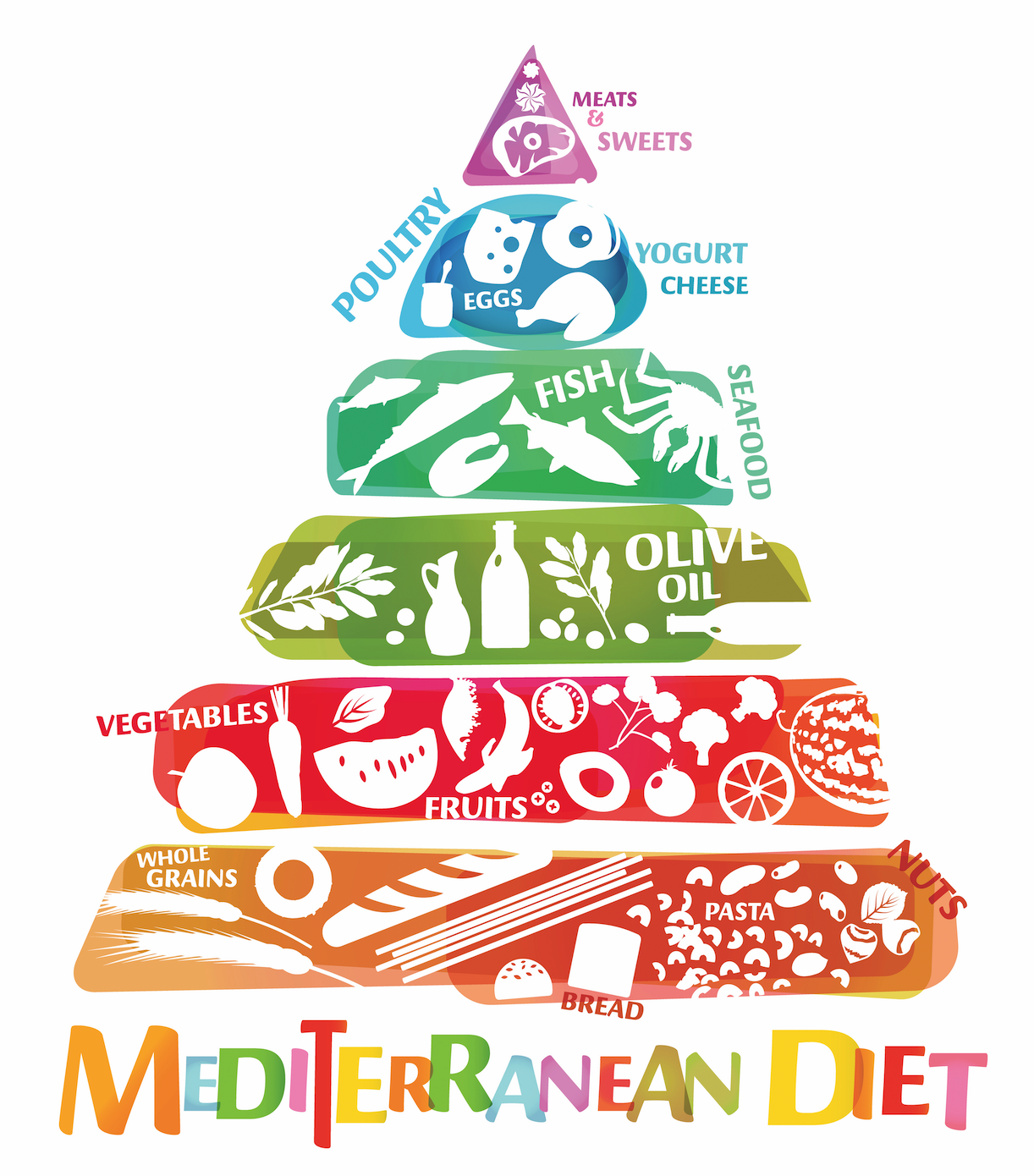

While we might not be able to manipulate our gut bacteria just yet, we do know that eating well may be associated with feelings of wellbeing. In 2018, a study published in Nature suggested that eating a Mediterranean diet rich in fish, nuts and vegetables could help lower a person’s risk of depression.

Researchers from Spain, Britain and Australia analysed 41 studies published within the last eight years on the links between diet and depression. Those who followed a strict Mediterranean diet had a 33 per cent lower risk of being diagnosed with depression compared to people who were least likely to follow these eating habits.

“There is some research that the Mediterranean diet may have some positive effects on mental health – and even if it doesn’t, it is thought to be good for your overall health,” says Chloe Hall, dietitian and spokesperson for the British Dietetic Association.

“Even if you struggle to adopt the Mediterranean diet fully, we can all adopt some of the habits, such as increasing the variety and amount of fruit and vegetables we eat, choosing wholegrain carbohydrates, using olive oil and increasing our intake of nuts, seeds and pulses, while reducing our intake of red and processed meat.”

Further study into how our gut-brain axis works and how gut bacteria affects our mental wellbeing is needed, as this research has only just begun.

“For a long time,” says Professor Raes, “people have seen gut bacteria as a source of evil – a cause of disease. But the outcome of these studies is that it can be hugely beneficial.

“I think what’s happening now is that we might take it one step further and we are going to take the bacteria from our gut and use them as medication – the bacteria becomes the drug against the disease, and that is an exciting prospect.

“There is a lot of work that needs to be done, but there is an interesting future ahead.”

A Mediterranean diet is good news for your gut

Foods for Better Gut Health

1. Fill up on fibre

You should aim for roughly 30g a day. You can get fibre from various sources, including wholemeal bread, brown rice, fruit and vegetables, beans and oats – these feed healthy bacteria in the gut.

2. Get your five a day

It’s recommended that you eat at least five portions of a variety of fruit and veg every day, which includes fresh, frozen, canned, dried or juiced. Just be aware of added sugar in some canned fruit.

3. Avoid junk

Highly processed foods can contain ingredients that reduce ‘good’ bacteria and increase ‘bad’ bacteria. Avoid them as much as possible.

4. Drink up

Water encourages the passage of waste through your digestive system. It is recommended to drink between six and eight glasses a day, and more if you exercise regularly and sweat it out.

5. Phase out fat

Try to avoid overly fatty foods and too much fried stuff, as it’s harder to digest and can cause stomach ache.

6. Say yes to yogurt

Probiotic foods, such as certain yogurts, contain live bacteria thought to be beneficial to us, and they may encourage more microbes to grow.