When it comes to forging physical and mental toughness, the man who spent 157 days swimming around the UK – battling deadly whirlpools, vicious storms and swarms of jellyfish – knows more than most.

Photo: Red Bull Content Pool

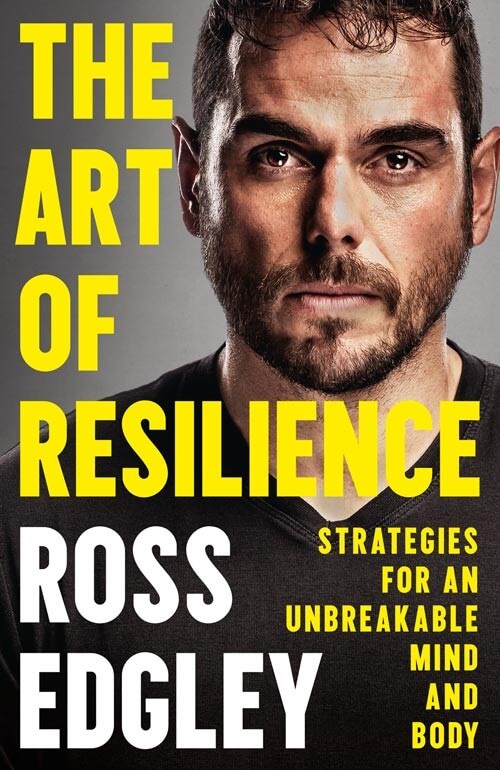

Ross Edgley combines a strongman’s physique with extraordinary endurance. He has rope-climbed the equivalent height of Mount Everest, towed a Mini Countryman for 26.2 miles, and in 2018 he became the first person to swim the entire coast of Great Britain.

In his new book, The Art Of Resilience: Strategies for an Unbreakable Mind and Body, Edgley reveals the inner secrets of mental and physical toughness that he discovered while training for and doing his larger-than-life endurance challenges.

MF caught up with him to find out how we can all apply these lessons to our own lives, and training, to build a resilient body and mind.

“A 12-inch baguette wrapped in a pizza – I would polish that off as a snack before swimming” | Photo: Red Bull Content Pool

Know What’s SAID

Edgley always applies a fair hunk of science to his endeavours, which makes him well-versed in the kind of conditioning he needs to do prior to a challenge.

“The SAID principle – Specific Adaptation To Imposed Demands – is key to everything I do,” he says. “In other words, you get really, really good at what you repeatedly practice.”

For Edgley, the media adulation of his Great British Swim feat missed the mark slightly: “The British media were amazing with the swim and they were saying, ‘God, look. Look how tough he is. Look at how resilient Ross is!’ I was like: ‘No, I’m just really good at floating and eating.’”

Indeed, when Ross first sought advice on how to become a better swimmer, he had a bioelectrical impedance analysis, and the lab techs told him that he was built like a hobbit, with dense bones and too much heavy, non-buoyant muscle mass.

“The sports scientist said, ‘You have a big, dense head. I replied, ‘I’ve got a big head?’ and they were like, ‘No, dense. You’re like a human submarine, with your head plummeting you into the seabed.’”

He puts his eventual, unlikely success down to his trained ability to eat a phenomenal amount of calories, before and after exercise, as well as specific adaptions to the swimming, due to the colossal volume he was doing.

He was putting away 15,000 calories a day: “A 12-inch baguette wrapped in a pizza – I would polish that off as a snack before swimming. People were like, ‘How do you eat and swim?’ I’m like, ‘How do you not eat and swim?!’”

Prior to his Great British Swim, Edgley put himself some gruelling Royal Marines training | Photo: Red Bull Content Pool

Think Like a Marine

Prior to the Great British Swim, Edgley did a non-stop, 48-hour swim at the Royal Marines Commando Training Centre, and they passed on a valuable lesson to him: “They told me, ‘You’re an athlete, so you’re used to performing at your best when you feel at your best, but we’re Royal Marines. We’re used to performing at our best when we feel our worst.”

At no point in the 157 days of his Great British Swim ordeal did Edgley wake up and feel fantastic: “It never happened. My tongue was hanging off, toenails were hanging off. One morning the bedsheets had fused to the open wounds on my neck – it was grim.

“Every single time I just thought: think like a Royal Marine. Perform at your best when you feel at your worst. Get in today and you might have one knot of current with you, so even if you just get in and stay afloat, if you’re in for six hours, you make six miles. It’s not great, but it’s better than nothing.”

Edgley swims past a cargo ship in the Dover Strait

Be a Scholar and a Savage

Edgley is a fan of what he calls stoic sports science, which can be applied across all sports and endurance activities, and is inspired by the resilient philosophy of the stoics.

“Imagine running a marathon,” he says, “and at 18 miles you hit the wall. Your legs are burning, your muscles are depleted of glycogen, your blood sugar levels are dangerously low, and you think, I cannot go on.

“But you keep running and you get to 25 miles, and you see your family and friends – they’re clapping. You can see the end and the crowds are cheering. All of a sudden you find a second wind. It’s like, hang on, what happened there? You said you were done at 18 miles?”

Edgley says this is down to what Tim Noakes calls the ‘Central Governor Theory’: “That fatigue is an emotionally driven state that we use to pull the physiological handbrake to stop us from doing harm to ourselves.” In other words, it’s negotiable.

When you are at your absolute physical limit, your ability to think is massively reduced. But for Edgley, the idea of stoic sports science boils down to whether you can summon the mental clarity to apply your knowledge, while your lungs are burning and legs are on fire, and stoically implement your game plan.

He remembers when he was running on empty, swimming past cargo ships as they swapped lanes in the Dover Strait, with bits of jellyfish hanging from his face:

“Can you ask: am I carbed up enough? Have 15 minutes gone? Am I refeeding? Is that chafing? Should I lube up my neck some more? What’s my pacing strategy? What’s my cadence like? Do I need to slow? What’s my heart rate doing? Am I aerobic or anaerobic?”

Can you actually do that? Because the majority of people can’t. Everything just goes out the window.”

Edgley is a master of the art of smiling through the pain | Photo: Red Bull Content Pool

Whatever Happens, Keep Smiling

Edgley has a robust sense of humour, and that comes in handy when facing mental ordeals.

“I think the next frontier of human performance actually lies in the head,” he says. ‘Cheerfulness in the face of adversity’ is written into the Royal Marines Commando ethos, and Edgley says the science backs it up – he gives the example of cyclists who rode to exhaustion but were shown subliminal cues of people smiling or frowning.

“They found those who were shown pictures of people smiling, cycled further and delayed the onset of fatigue longer than those who were shown pictures of people frowning.

“You know, Ernst Shackleton, during his polar expeditions, kept a Christmas pudding in his sock, and would whip it out to boost morale at key points. I call it the science of the smile.”

Hone in on what you want to achieve, says Edgley, and be specific with your training | Photo: Red Bull Content Pool

Ask Yourself What You’re Drilling

When it comes to training and improving your own performance, Edgley says it’s vital to hone in on what you actually want to achieve, then reverse engineer it back from there, but be brutally specific.

“If you want to be a good runner, run,” he says. “If you want to be a good cyclist, cycle. The Bulgarians produce more Olympic and World Champion weightlifters than any other country in the world, yet Bulgaria is tiny. Their methods are just like, ‘You will lift. You will clean and jerk and snatch. You might front squat, but if I catch you bicep-curling there will be hell to pay! No, no, no you’re going to be so specific.’

“Whatever you’re training for, you cannot ignore the laws of biology, physiology or biomechanics. There’s a modern trend that means we want to believe in the idea of a hybrid athlete, but the science just doesn’t support that.

“Even with CrossFit, when you look at the modern greats like Mat Fraser, they have an Olympic-lifting background. That’s why they’re good at CrossFit!”

Of course, strength training for endurance efforts (to counter overuse and prevent injury) does have its place, but Edgley says that too many different inputs will nerf your training:

“I think too many people are too general. When you’re training for too many things in one session, you dilute the potency of the stimuli.

“People go into the gym and do a 5km run on the treadmill, but then they’ll see their friends in the corner hitting squat PBs, so they’ll go and squat as well. On a cellular level, your body doesn’t actually know what it’s adapting to – it’s so confused! A training programme that’s designed to train for too many things at once is a training programme that trains nothing, basically.”

Order your copy of Ross Edgley’s The Art Of Resilience: Strategies for an Unbreakable Mind and Body from Harper Collins. Follow him on Instagram @rossedgley

Words: Matt Ray