Elite sport is usually about winning at all costs, so what does it mean to be a professional loser? Writer Mark Turley spent a year meeting with journeymen boxers to find out.

The scene at the iconic York Hall in Bethnal Green is typically chaotic, both tiers packed, the crowd divided into sections. Essex wideboys in one, Irish mad men in another. Football songs, designer clobber, lines of cheap coke in the toilet. Subdued violence hangs in the air like a fog.

Amidst all that, in the ring, the actual, regulated violence – a boxing match – is about to start. Clad in shiny shorts and robe, one of the fighters grins, bouncing from foot to foot. The bow-tied MC introduces him: “Tonight ladies and gentlemen, making his debut…” and the kid swivels on his hips and scowls theatrically. His contingent of fans go crazy, screaming, punching the air. One of them blows an airhorn.

By contrast, when the other boxer is introduced, the hall falls into eerie silence. His name is Johnny Greaves, a local boy from London’s East End, but few seem bothered about that. We are told he is a veteran of more than 90 fights. Fair enough, but when the MC goes on to state that Greaves has won just three of them, a few groans and even some mocking laughter can be heard.

Then the bell rings, the action starts and something becomes quickly apparent. Despite his catastrophic numbers, Greaves is no-one’s mug. He is crafty and elusive – he tucks his chin behind his guard and stays mobile. He absorbs very few full-blooded shots. When they do get through, he swallows them like blobs of ice cream.

Sometimes he goads his opponent, talks to him, makes faces. At one point he spontaneously jives his feet in an Ali shuffle to the crowd’s great amusement. He doesn’t attack much, spending most of the fight on the back-foot, but Greaves looks like he’s enjoying himself.

As the action ends and the decision is announced – a wide points defeat, he gives a resigned smile, pats his conqueror on the back and struts out of the ring. The crowd shout things. Mostly not very nice things. Greaves just swaggers past.

Twenty minutes later he’s in the bar with a slightly swollen lip, a pint of lager and a twinkle in his eye.

Journeyman boxer Johnny Greaves (right) takes a hit from Tony Owen | Photography: Philip Sharkey

Meeting The Journeymen Boxers

Six months on from that night, I arranged a meeting with Johnny Greaves at the famous Peacock Gym. Set on an uninspiring trading estate beneath a flyover in Canning Town, the place holds a mythical position in British fighting folklore. Everyone has trained there at one time or another. On the forecourt outside reception stands a statue of 24-year-old Bradley Stone, a monument to the dangers which lurk within. Stone died of a brain haemorrhage after a British title fight in 1994.

Inside, over coffee, the battle-worn Greaves quickly dispelled a few stereotypes. He may have had scarred eyebrows, a nose that could be used to teach schoolkids about obtuse angles and disfigured, lumpy hands, but he was also self-deprecating, easy to talk to and witty.

Greaves told me about his childhood, how he had always fought. For him it was a form of self-expression, in the same way that other kids drew pictures or played football. It was the one thing he was good at. The thing that made him, him.

He had grown to become British champion on the unlicensed circuit and when he turned pro, in 2007, found himself with a straight choice. Box in the home corner, his manager said, sell at least 80 tickets, start on purses of a few hundred quid and work his way up, or box ‘away’, as a journeyman. The latter meant no ticket sales. Just turn up, fight and get up to a grand and a half a night.

Greaves grinned at me. “I was never going to be world champ, so it was a no-brainer.”

But what exactly does it mean to be journeymen boxers? Greaves explained it like this: “I keep busy and I’m well known around the scene. Of course, I don’t go in there to lose – not exactly. But if you upset the ticket sellers, the promoters won’t use you. If you want the regular work, you need to understand your role, if you see what I mean.”

I wasn’t sure that I did.

“To be really in demand,” Greaves went on, “promoters like a good fight. They want their boy stretched. You can’t just go in and fall over at the first punch. What you need to do is give the kid a workout, entertain the crowd and last the distance. Then they feel they’ve got their money’s worth. It’s a difficult thing to get right, but if you can do that week in, week out, you make a decent living.”

In the space of a few minutes he had introduced me to the journeyman holy trinity: stay competitive. Don’t get hurt. Don’t win.

That’s not as easy as it sounds.

Johnny Greaves retired after 96 losses from 100 fights | Photography: Elisa Scarato

Journeymen Boxing Is A Business, Not A Sport

I spoke with Greaves many more times, to the extent I came to think of him as a friend. There was a definite tinge of self-destructiveness there. He was open about his mental health problems and flirtations with booze and drugs. Incredibly Greaves smoked 20 a day throughout his career, eventually retiring from the journeymen boxers after his 100th bout, with 96 defeats to his name. He was also on prescribed medication for depression, although he insisted that boxing had nothing to do with it.

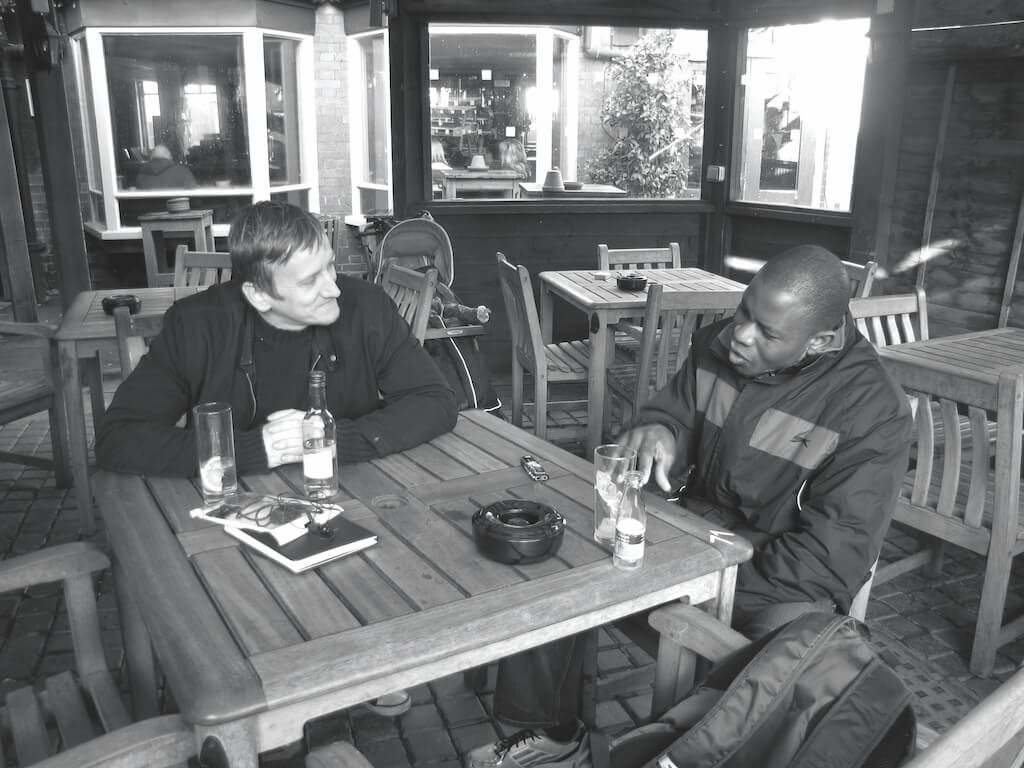

Over the ensuing months I travelled around the country, meeting nine further journeymen boxers who fulfilled a similar role. Another who intrigued me was a South African lightweight living in south London, called Bheki Moyo. We met in a local pub.

On the surface Moyo’s most striking characteristic was his record: 67 losses and two draws from 69 bouts. Even by journeyman boxing standards, having no wins at all was unusual. Most away corner boxers got the occasional ‘W’, to avoid negative attention from the Board of Control.

He sighed when I brought it up. “I didn’t understand the business at all.” He said in his lilting accent. “And it’s really a business, not a sport. They put me in the away corner. I accepted it because I didn’t know what it meant. In several fights I thought I clearly won, was even hurting the other guy, but not getting the decision.”

The Dark Side of Journeymen Boxing

As a naive young fighter, Moyo had encountered the other journeyman quandary. In a system ruled by money, referees are also booked and paid by the promoter. Like everyone else, they understand the power structure and a ref who habitually awards decisions to the away corner will find himself unpopular. This means that for journeymen boxers, opening up and risking injury – trying to win – is often pointless.

Just like Greaves, Moyo grew up fighting. “As a kid I loved boxing,” he said. “I thought it was glorious.” Then his expression changed. “Now I don’t. Here we are as a species, humankind. We have evolved with an organ that makes us unique, our brains. Why do we see glory in a sport that aims to damage the brain? What is the aim?”

It was a little shocking. I had a never heard a boxer speak like that before.

“Most of the crowd,” he went on, “they don’t appreciate what they’re seeing. They just want blood, they want to see brain damage, because that’s what a knockout is.” He shook his head. “I can no longer support a sport like this.”

Moyo told me he was studying a law degree and spoke at length about global inequalities and the environment. He was excited by the Occupy protests taking place around the world. At the same time, however, I noticed how his hands shook as he raised his glass.

Brutal Business

Moyo boxed on for another year after our first meeting, to cover living expenses while finishing his course. He clocked up 75 bouts in all. We met several more times and interacted online. He was anxious about his studies (despite doing well), struggled with exam pressure and talked a lot about depression. The state of the world distressed him while he also pondered the neurological damage he may have sustained through boxing.

As time went by, all ten fighters that I met that year retired from the ring. Some like Johnny Greaves or Nuneaton’s Kristian Laight, who boxed a staggering 300 contests (12 wins), seemed relatively unscathed, but not all were so fortunate. One suffered an anomaly on a brain scan. At least two had unclear speech. Others spoke of memory loss. Nearly all seemed disappointed with their careers. Five grand a month or so is decent going, but once it was over, many journeymen seemed haunted by thoughts of ‘what if?’

The quid pro quo of earning four figures a week was to give up the things that lie at the heart of athletic competition: hope, ambition, the anticipation and joy of victory. For them, boxing had only been a job.

“If I’d chosen the other way, got off the booze and fags, who knows?” Greaves told me, eyes full of sudden sporting pride. “I went in with three world champions and about ten British champions and I never finished a fight on my pants. That tells you something.”

Sheffield’s Daniel Thorpe (113 defeats) agreed. “The money’s great for journeymen boxers,” he said, “but it can be tough mentally.”

I spent many nights thinking about that dichotomy and how it reflects so much about sport in the modern world – money, or passion? Then in March 2017, Bheki Moyo posted a message on Facebook. ‘I see a world heading in

the wrong direction…I have to sleep now. I love you all.’

The police found his body in a park later that night. Local news reported problems with the home office, even a possible deportation, but no-one really knew what made him do it.

Mark Turley with the late Bheki Moyo (right). Moyo’s tragic story lays bare the brutal lives led by boxing’s forgotten men, the journeymen boxers | Photography: Elisa Scarato

Choosing to Lose As A Journeyman Boxer

I still often think of Bheki Moyo, the pro who never won a fight. I remember his eloquence, his unique take on the sport he once loved, all his talk of injustice, and those slightly shaky hands.

The conversation around mental health in boxing has grown in recent years. Even fighters with solid defences, who avoid serious injury, will suffer multiple ‘sub-concussive traumas’ and these can have a creeping effect. As research develops, it is natural that the spotlight will fall on those who box often and over long periods of time.

While this process evolves, it might be nice if more fans appreciated what journeyman do, along with the incredible physical and mental pressures it entails. Perhaps if they did, they wouldn’t be so harsh.

When I think back to the journeymen bowers I met, the choices they had to make, the stresses they faced and all the contempt they endured, I have nothing but respect for them.

They perform probably the most gruelling role in professional sport.