British climber James Pearson battled slippery rocks and thundering spray to conquer the highest waterfall in Japan.

He talks to Mark Bailey about the unique sport of Sawanobori (‘stream climbing’) and reveals how to steel your body and mind for vertical adventures.

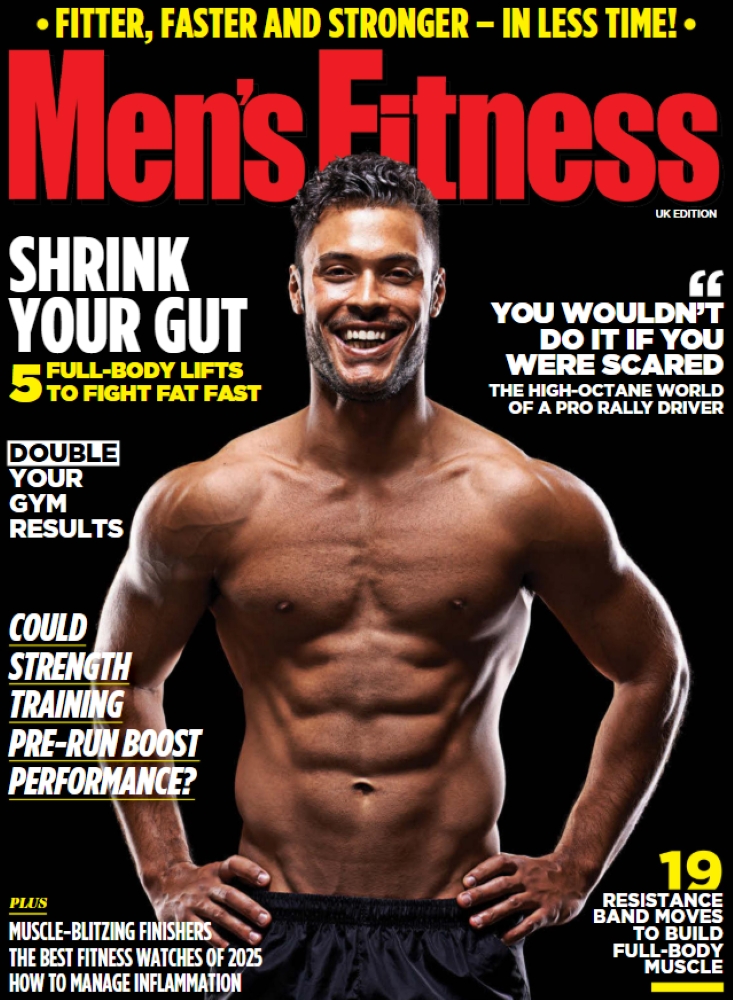

©The North Face

On his epic climbing expeditions around the world, from the sandstone towers of Chad to the overhanging cliffs of Borneo, James Pearson instinctively avoids the one element all climbers fear: water.

This life-giving liquid can be lethal for climbers: rain fatally loosens climbing holds, rivers silently erode the stability of rocks, freak storms wash away fixed ropes, and even a trickle of sweat can cause strained fingers to slip from stone.

But in August 2018 the 33-year-old professional climber from Matlock rewrote the rulebook by ascending the booming, spray-soaked Shomyo Falls – at 1,148ft, the tallest waterfall in Japan.

Men’s Fitness: How would you describe the sensation of climbing a thundering 1,000ft waterfall?

James Pearson: “Climbing waterfalls is a real sensory overload. It was very intimidating even to start some of the climbs in Japan, just because of the power of the water. And then when you go into the waterfall for the first time and feel its physical power on you, you feel so small and helpless.

“With some of the bigger waterfalls, like Shomyo Falls, you can’t climb too close to the water, especially near the bottom where the water is strongest. There is a drop of 150m. And when you imagine three tonnes of water dropping every second, by the time it’s near the bottom it is incredibly powerful.

“If you went too close, you would die. It would wash you away. It would rip all your gear out. I am pretty sure it would rip your ropes, too. It can also be hard to hear any loose rock and the holds are really slippery.

“So Sawanobori teaches you to be quite humble to the power of Mother Nature. I am maybe too much of a poet, but I feel like that is a good lesson: we can enjoy Mother Nature, but

if we don’t show her enough respect, she can wipe us out.”

MF: Sawanobori is an important part of Japanese climbing culture, but it’s not well known around the world. What does it actually involve?

JP: “When you talk about Sawanobori, most people think you’re crazy. They think maybe one and a half people might be doing it somewhere in the world as some zany pastime, but in Japan it is a serious part of mountaineering culture.

“Japan is covered in dense vegetation and for years the easiest way to move between villages was to go via the rivers, so Japanese climbers have been doing it for hundreds of years.

“Today, Sawanobori involves climbing up a river and all its waterfalls and streams, while staying as close as you can to the water. You go against the flow, just wading, swimming and climbing.”

MF: When did you first start thinking about climbing waterfalls?

JP: “About ten years ago, on one of my first North Face Athlete Summits, a famous Alpinist called Greg Child proposed a canyoning trip in Hawaii. But some of the Japanese athletes on the team said, ‘You could try climbing up the canyon instead.’

“We all laughed because we thought something must have been lost in translation. But it turned out that climbing up canyons or waterfalls is really a big thing in Japan. When I got to know the Japanese climber Toru Nakajima, he told me he had spent the summer climbing waterfalls.

“I thought he meant ice-climbing frozen waterfalls. But he said: ‘No, wet waterfalls.’ That’s how Sawanobori began for me. I was so intrigued, I had to try it.”

MF: What were you most concerned about before the expedition?

JP: “Climbers like me, who grow up on gritstone in the Peak District, are very sensitive to rock conditions. We moan a lot. And we don’t like it too hot or cold or humid because your contact with the rock is all-important.

“If the conditions don’t feel good, the moves are ten times harder. So going climbing somewhere that was wet all the time seemed really stupid. But once you accept that you’re going to spend the whole day climbing up wet, mossy waterfalls, it becomes something really cool.”

MF: What were the most extreme conditions you faced?

JP: “In addition to all the issues with wet rocks, you are also wearing a wetsuit. And it is pretty grim. A wetsuit is heavy and awkward to move in but a lot of these rivers are glacially-fed so if you didn’t wear a wetsuit you would freeze.

“A few times I experimented with wearing different equipment but I always got it wrong. We’d wear just a baselayer for north-facing, glacially-fed waterfalls so we’d freeze to the point that we had to get those special silver space blankets out because some of us were feeling hypothermic. And then we’d wear a wetsuit for south-facing waterfalls which bake in the sun so we’d basically boil and get heat stroke.

“When you get it right, it is pleasurable. When you get it wrong, it is hell.”

MF: Any close calls?

JP: “On one of the first ascents, I crossed over and through the waterfall, which was already pretty insane, but I got into this really tricky place. I was on the other side of this torrent so I didn’t want to turn back: I had no fixed gear and a down-climb was unthinkable. So I had to push on.

:But I was getting further and further away from security and suddenly the only thing I could grab onto was some viney roots from a plant growing out of the rock. I remember gently tickling these roots, wondering if I could pull on them.

“I had to do this one move that would get me to a good hold. So I spent ten to 15 minutes contemplating whether to commit. When I finally went for it, the roots stayed in place but I quickly realised the good hold I was hoping for didn’t exist. So I had to find some more roots to hold.

“A few moves later I had roots in both hands and I was basically attached to the wall only by the plants growing on it. I realised afterwards what an insane situation that was.”